The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

Evolutions in Modern Warfare

Note: I first produced this analysis this for the U.S. Army's now-defunct Asymmetric Warfare Group in early 2021. AWG later released the IP back to BT Consulting LLC in October 2021.

Executive Summary

This is an open-source analysis of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War. This product does not provide a play-by-play review of the conflict. Rather, it focuses on novel and otherwise significant uses of various military technologies and tactics, as well as noteworthy vulnerabilities and operational shortcomings. Key findings are below.

The air war:

Manned aviation assets saw little combat and only in the early days of the conflict. Turkish F-16s present in Azerbaijan likely served as a deterrent against Armenia using its own aircraft.

Turkey sent advisors to Azerbaijan who shared the lessons of Turkey’s experiences using unmanned aerial systems (UAS), loitering munitions, and electronic warfare (EW) in Syria and Libya. Azerbaijan copied these tactics, particularly using the Bayraktar TB2 and Harop loitering munition, to attack Armenia’s air defenses and ground forces.

Most Armenian air defense systems were antiquated and unable deal with these unmanned threats. Russia provided some EW assistance, but it occurred too late in the conflict to be consequential.

The land war:

The land war oscillated between maneuver and positional warfare. Azerbaijan’s repeated and coordinated use of UAS, loitering munitions, rocket artillery, and missiles enabled its ground forces to slowly take and hold territory, while denying Armenia the chance to adequately reinforce and resupply its beleaguered frontline forces.

The proliferation of sensors on the battlefield made it difficult for Armenian armor and other ground forces to conceal their positions. In addition, these formations lacked sufficient air defense capabilities and suffered inordinate losses as a result.

Both sides employed rocket artillery and missiles against military and non-military targets at various levels of war, and from close fighting to strategic support zones. This indicated a lack of concern for collateral damage.

Turkey supplied Syrian fighters to support Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh, but their effect appeared negligible. Limited reporting indicated that volunteers from the Armenian diaspora might have participated as well.

The information war:

The information war was multifaceted, involving the governments of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey, as well as press outlets and legions of social media users. Both accurate and fabricated information proliferated globally throughout the conflict, leading to confusion at tactical, operational, and strategic levels.

For the entirety of the conflict, Azerbaijan selectively restricted Internet access, blocking most social media platforms inside the country. This represented the war’s most coordinated effort to control the information environment.

Azerbaijan’s use of UAS camera footage depicting strikes on Armenian vehicles and positions was the most visible element of the information war. However, the videos resulted in distorted views on battle damage assessment (BDA).

Cyber attacks were commonplace during the conflict, with attacks on government and private websites, as well as a potential attack on numerous flight tracking websites, possibly to obscure the movement of military aircraft at the onset of the war.

All sides engaged in “lawfare” to shape the information environment. Azerbaijan, by far, had the best coordinated, most wide-ranging effort.

The following are noteworthy lessons learned for future conflicts:

A combination of UAS/loitering munitions provides much of the functionality of a traditional air force, but at a much lower cost. Therefore, such capabilities are no longer the purview of wealthy nations.

Many modern air defense systems are ineffective against slow-flying UAS/loitering munitions.

Sensors pervade the modern battlefield to such an extent that it is difficult to achieve effective cover and concealment, leaving ground formations vulnerable to detection and attack. Ground formations without organic air defenses, in particular C-UAS, likely will not survive this environment.

Long-range fires remain viable against frontline formations, operational reserves, and strategic support zones.

Information warfare is so pervasive it is difficult to separate fact from fiction.

Introduction

This is an open-source analysis of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War. This product does not provide a play-by-play review of the conflict. Rather, it focuses on novel and otherwise significant uses of various military technologies and tactics, as well as noteworthy vulnerabilities and operational shortcomings. By design, this product does not supply recommendations. It simply provides data and analysis on the conflict that can be of use to various institutional elements of the U.S. Army. Lastly, the report references geopolitical and policy matters only to the extent necessary to provide sufficient context in which to discuss relevant military dimensions of the conflict. Much more could be said on those topics, but such a discussion is beyond the scope of this project.

Sources include government reports and press releases, media reports, and analyses from regional and topical experts. As with any open-source product, this one certainly does not tell the whole story and it is difficult to confirm the veracity of information contained within all sources. This product contains no classified or Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI).

Terminology:

The paper refers to the region in question as “Nagorno-Karabakh” (mountainous black garden) instead of the “Republic of Artsakh,” as the latter refers to a largely unrecognized political entity. In addition to Nagorno-Karabakh, much of the fighting occurred in seven adjacent Azerbaijani districts (refer to the map.) Except where noted, this paper refers to the entire conflict zone as Nagorno-Karabakh, as control over this territory is the original impetus for the conflict.

The term “Azeri” refers to the ethnic group that comprises over ninety percent of the Republic of Azerbaijan’s population. To avoid confusion between this ethnic group and the country’s population as a whole, this paper uses the adjective “Azerbaijani” and not Azeri to describe that country and its military forces.

Most reporting fails to distinguish between the forces of the Republic of Armenia and those of the pro-Armenia separatists in Nagorno-Karabakh. Often there appeared to be no actual distinction between the two on the ground. Therefore, this report generally refers to this side as “Armenia” and “Armenians,” unless otherwise noted.

Lastly, the paper uses short-form names when referencing most other countries, past and present: the defunct Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is the “Soviet Union;” the Russian Federation is “Russia;” the Republic of Turkey is “Turkey;” the State of Israel is “Israel;” and the People’s Republic of China is “China.”

The remainder of the document is laid out as follows: An introductory chapter sets the stage with historical context and an explanation of the involvement of the Russia and Turkey. The next three chapters examine the conflict as the air war, the land war, and the information war, respectively. This is merely an organizational framework in which to isolate items by topic. It does not imply there were separate conflicts—all three occurred in tandem. Moreover, this structure is not meant to detract from the multi-domain nature of modern warfare or the necessity of integrated operations. The penultimate chapter examines the multiple ceasefire attempts, reactions to the post-war status quo, and evidence of how the conflict could have turned into a much wider, regional war. Lastly, there is a conclusion.

Background

Overview of Conflict and Timeline

The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War took place from September 27, 2020 to November 10, 2020. The forty-four-day conflict saw two former Soviet republics resume their deadly conflict that had raged intermittently for decades. For most of this time, Armenia maintained military overmatch and occupied superior terrain. Since the late 2000s, Azerbaijan used oil revenue to fund a substantial military modernization program, including the acquisition of sophisticated weapons from Israel, Turkey, and others. Moreover, Turkey provided Azerbaijan invaluable advisory assistance, particularly in the use of UAS and loitering munitions to degrade enemy air defenses and strike ground targets. These additional weapons and knowledge proved determinative, and Azerbaijan was able to regain some of the territory it had lost to Armenia in previous fighting. The fighting also included long-range fires against military and non-military targets, as well as an intense information war. The fighting ended by way of a Russian-brokered ceasefire. Approximately 5,000 soldiers and hundreds of civilians died in the fighting. [2]

Timeline of events:

September 27, 2020—start of hostilities

September 27, 2020—Azerbaijan initiated domestic media restrictions

October 10, 2020—first ceasefire agreement

October 26, 2020—second ceasefire agreement

November 9, 2020—final ceasefire agreement

November 10, 2020—end of hostilities/final ceasefire began

November 10, 2020—protestors storm Armenian parliament

November 12, 2020—Azerbaijan ended domestic media restrictions

December 10, 2020—Azerbaijan held a victory parade

January 30, 2021—joint Russian/Turkish operations center became operational[3]

Historical Context

Nagorno-Karabakh is a mountainous region in the South Caucasus consisting of about 1,700 square miles.[4] According to data from 2014, the population of approximately 145,000 consisted primarily of Christian Armenians (nearly ninety-five percent) and a Muslim Turkic people known as Azeris.[5] Armenia and Azerbaijan have disputed ownership of the territory since 1918 when both Armenia and Azerbaijan declared independence from the Russian Empire. By the early 1920s, the newly founded Soviet Union had conquered the region, absorbing Armenia and Azerbaijan, and making both Soviet Socialist Republics. Despite its ethnic Armenian majority, Nagorno-Karabakh became an autonomous administrative region within the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic.[6]

In 1988, near the end of the Soviet reign, Nagorno-Karabakh’s regional legislature voted to join the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, but the move failed to gain recognition in Moscow. A six-year regional war ensued in which an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 people died and one million were displaced. Armenian separatists declared Nagorno-Karabakh an independent country, the Republic of Artsakh. The would-be nation failed to gain international recognition, save from a handful of other former Soviet, unrecognized, breakaway republics. Nonetheless, the separatists not only held control of Nagorno-Karabakh, but also captured seven adjacent Azerbaijani districts.[7]

The conflict came to an end when the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) brokered a peace deal in 1994. This occurred though a multi-country entity known as the Minsk Group, which U.S., France, and Russia co-chaired. However, lasting peace remained elusive as ceasefire violations occurred regularly thereafter.[8] According to the Council on Foreign Relations:

Because Azerbaijani and ethnic Armenian military forces are positioned close to each other and have little to no communication, there is a high risk that inadvertent military action could lead to an escalation of the conflict. The two sides also have domestic political interests that could cause their respective leaders to launch an attack. [9]

Between 1994 and 2020, the most significant combat occurred from April 2-5, 2016. The conflict became known as the “Four-Day War” and an estimated two-hundred people died.[10] During the fighting, both sides employed artillery, tanks, UAS, and special operations forces (SOF), among other assets. Azerbaijan was able to seize, “a number of strategically important heights.”[11] This marked Azerbaijan’s first reclamation of lost lands, albeit a small gain.[12] Armenians remained in control of most of the territory they had gained in the preceding decades.

From 1988 until the early 2010s, Armenia and its separatist allies had the advantage of occupying superior terrain, and also of having a generally superior force in terms of leadership, motivation, and agility.[13] However, since the late 2000s, Azerbaijan used its cash reserves, obtained largely from oil sales, to modernize its military. Azerbaijan acquired many new weapons systems, principally from Turkey, Russia, and Israel. Purchases included more advanced missiles, rocket artillery, loitering munitions, and UAS.[14] The result was that Azerbaijan had achieved a significant qualitative advantage.[15]

Other Actors

The official belligerents in the conflict included the Republic of Azerbaijan, on the one side, and the Republic of Armenia and the unrecognized Republic of Arstakh, on the other. However, other actors were involved to varying degrees. This section introduces the very subdued role of Russia and, by contrast, Turkey’s active participation. Both countries’ involvement is described in greater detail in the appropriate chapters.

Turkey

As Turkic peoples, Turkey and Azerbaijan share a common ethnic heritage. Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan goes beyond mere brotherhood. Turkey provides political and diplomatic support, as well as weapons and military assistance. Due to Turkey’s extensive involvement in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War—the most of any country other than Armenia and Azerbaijan—Turkey figures prominently throughout the remainder of this report and requires no further discussion in this section.[16]

Russia

Russia and Armenia, along with Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, comprise a security alliance known as the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Among the CSTO’s statutory obligations is a mutual security guarantee.[17] From the start of the most recent conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated publicly that Russia would honor its commitment to defend Armenia should that country be attacked, but that Russia would not intervene in fighting outside of Armenia’s internationally recognized borders (i.e., in Nagorno-Karabakh and the seven adjacent territories Armenian forces occupied.)[18]

In addition to Armenia’s security relationship with Russia via the CSTO, the two nations have bilateral military relations. First, Russia operates the 102nd Military Base in the Armenian city of Gyumri. Second, Russia has an airbase at Yerevan’s Erebuni Airport.[19] Third, in 2015 Russia and Armenia entered into a joint air defense agreement.[20] Lastly, Russia maintains border guards in Armenia due to a 1992 treaty. These guards are part of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB or Federal'naya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti.)[21]

Despite having such a robust security presence in Armenia, Russia never openly entered the conflict. Several events could have prompted Moscow’s direct involvement in the conflict. Examples include the following:

On October 14, Azerbaijan admittedly struck missile launchers based inside the internationally recognized borders of Armenia, claiming attacks on Azerbaijani cities had occurred from the site. Although this constituted an attack on Armenia proper, Russia did not use the incident as a reason to invoke its mutual defense obligation under the CSTO.[22]

On November 9, Azerbaijan shot down a Russia military Mi-24 helicopter in Nakhchivan, near the Armenian-Azerbaijani border. Azerbaijani forces fired a man-portable air defense system (MANPADS), which brought down the aircraft and killed both crew members. Azerbaijan took responsibility, apologized to Russia, and offered to pay compensation to the families of the victims.[23]

That Russia did not intervene publicly on behalf of Armenia seems to indicate a strong reluctance to do so, particularly after Azerbaijan struck targets inside Armenia.

This leaves the question of whether Russia participated in the conflict in less visible ways, but scant reporting exists to address this issue. For instance, some reporting indicated Russian border guards had moved from their regular posts and taken up new positions along the border with Nagorno-Karabakh, possibly to provide aid to Armenia, and potentially suffering casualties. The Russian government provided no clarification.[24] Open-source reporting is almost always an inadequate means to evaluate covert and clandestine actions, as well as intelligence activities. This project is no exception.

The Air War

Key Points

Manned aviation assets saw little combat and only in the early days of the conflict. Turkish F-16s present in Azerbaijan likely served as a deterrent against Armenia using its own aircraft.

Turkey sent advisors to Azerbaijan. These individuals shared the lessons of Turkey’s experiences using UAS, loitering munitions, and EW in Syria and Libya. Azerbaijan copied these tactics, particularly using the Bayraktar TB2 and Harop loitering munition, to attack Armenia’s air defenses and ground forces.

Most Armenian air defenses systems were antiquated and unable deal with these unmanned threats. Russia provided some EW assistance, but it occurred too late in the conflict to be consequential.

Overview

Both sides made little use of manned combat aviation and only did so in the beginning of the war. Turkey had F-16 fighters based in Azerbaijan for several months before the war began. The fighters were to serve as a deterrent against Armenian ground attack aircraft.[25] In early October, Armenia claimed a Turkish F-16 shot down one of its Su-25s.[26] Manned aviation played virtually no role in the war thereafter.[27]

The highlight of the air war, by far, was Azerbaijan’s use of UAS and loitering munitions. These systems allowed Azerbaijan to penetrate and effectively neutralize Armenia’s antiquated air defenses, particularly in the south where terrain was more favorable to the Azerbaijanis. With virtual air superiority, Azerbaijan used its unmanned fleet to degrade Armenia’s fixed positions and maneuver formations, paving the way for incremental territorial gains.[28]

The remainder of this section discusses UAS and loitering munitions, as well as air defense.

UAS and Loitering Munitions

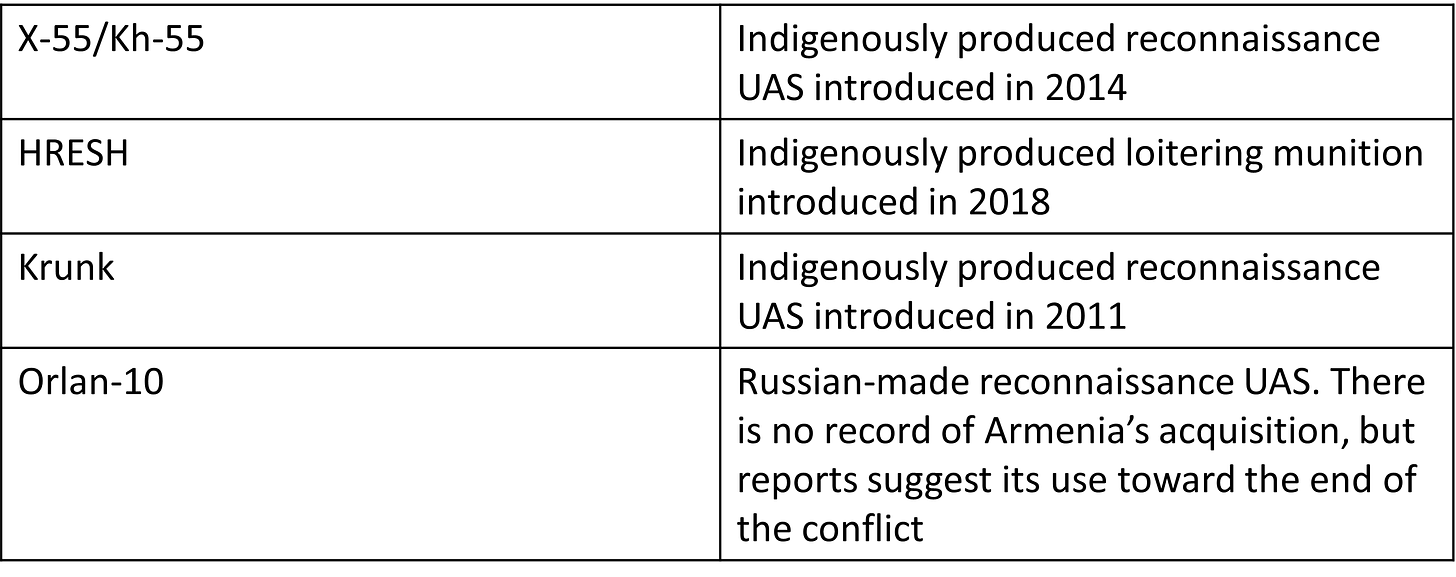

Armenia’s UAS fleet consists primarily of indigenously produced systems except for the recently acquired Russian Orlan-10. These systems are focused on reconnaissance missions. The table below, adapted from a product by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, presents estimates of Armenia’s pre-war inventory.[29]

Table 1: Armenia’s UAS and Loitering Munitions

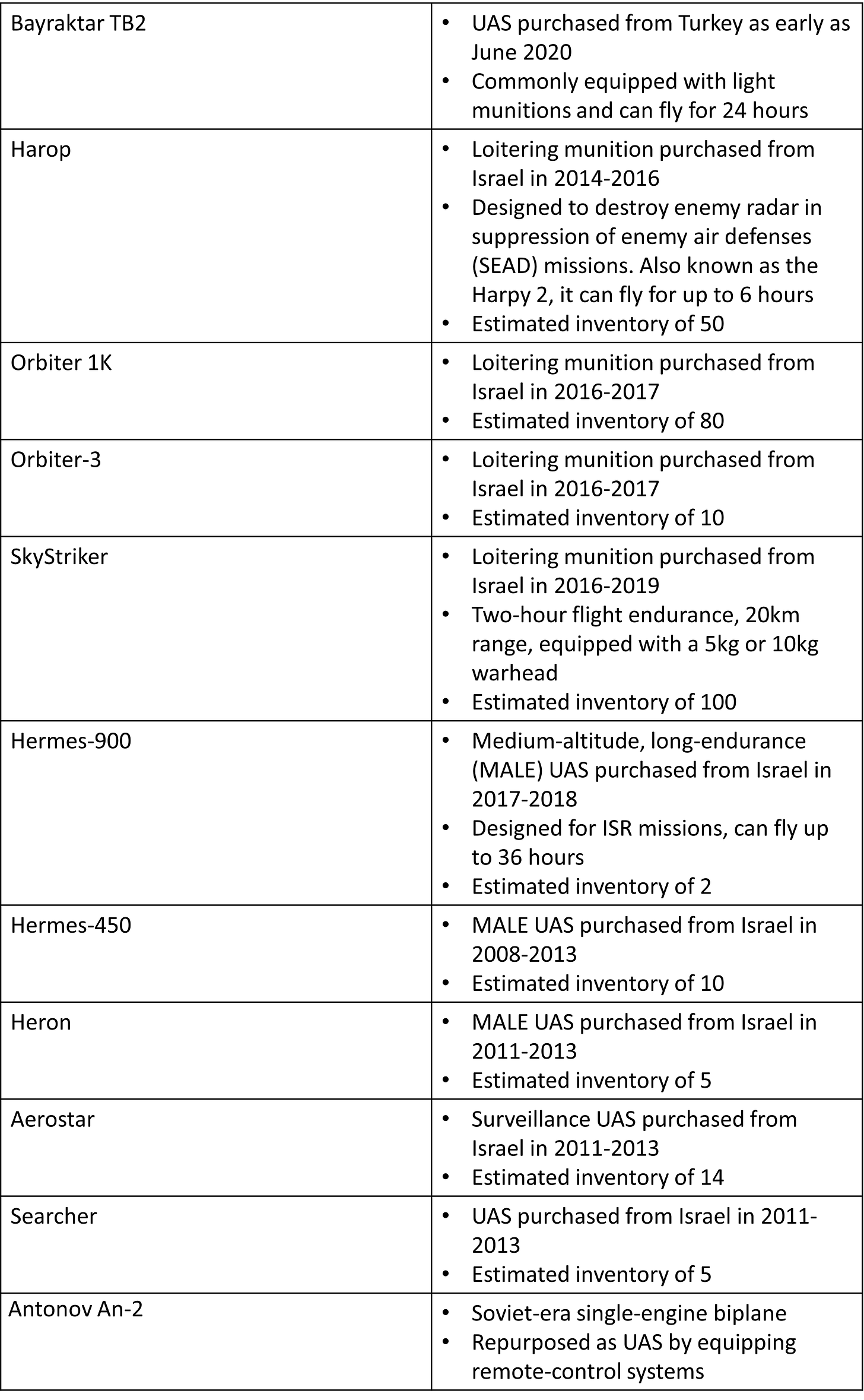

Azerbaijan’s UAS arsenal, in contrast, is much more robust and diverse. It includes advanced systems purchased from Turkey and Israel. In addition, Azerbaijan has numerous Israeli loitering munitions.[30] The table below presents estimates of Azerbaijan’s pre-war inventory.

Table 2: Azerbaijan’s UAS and Loitering Munitions

A discussion of the air war in Nagorno-Karabakh must first begin with the Turkish experiences in Syria and Libya in 2020.[31] During “Operation Spring Shield,” in late February and early March 2020, Turkish forces attacked elements of the Syrian Arab Army (SAA). Using the Bayraktar TB2 and Israeli Harop loitering munition, among other weapons, Turkey wreaked havoc on its foe.[32] In addition, Turkey used an EW complex known as KORAL to, “intercept and deceive radar systems in Syria,” and was able to destroy several Russian-made Pantsir S-1 and Buk air defense systems.[33] A similar episode unfolded months later in Libya where Turkey again employed Bayraktar TB2s, Harops, and EW to destroy Pantsir S-1 systems and attack the forces of Khalifa Haftar.[34]

Turkey, “exported this expertise in the form of military advisors to Azerbaijan.”[35] Azerbaijan already had experience using the Harop. In the 2016 “Four-Day War,” Azerbaijan used a Harop to destroy a bus of Armenian soldiers.[36] Azerbaijan acquired the Bayraktar TB2 as early as June 2020. These UAS were pivotal in destroying fixed and mobile targets, including air defense systems, artillery, tanks, and armored personnel carriers.[37] In addition, Azerbaijan retrofitted the An-2, a Soviet-era biplane, with remote-control systems. It then used these aircraft as bait to force Armenian air defense systems to emit active radar signals, allowing the Azerbaijan to destroy the systems with more advanced UAS, including the Bayraktar TB2.[38]

A key lesson of this war, as well as the wars in Syria and Libya, is the cost-benefit of employing UAS and loitering munitions. Countries that are unable to afford sophisticated air forces can instead purchase relatively cheap unmanned weapons capable of achieving similar results, including precision strike, without the potential loss of valuable aircrews.[39]

Air Defense

Azerbaijan’s aerial onslaught was coordinated and effective.[40] However, other factors, some structural and others tactical, contributed to the collapse of Armenia’s air defenses. Most of Armenia’s systems are legacy Soviet platforms designed to strike down, “fast-moving fighters, and their moving-target indicators disregard small, slow drones.”[41] More effective systems, such as the Buk and Tor-M2KM perhaps shot down several drones but Armenia deployed these too late for them to have had a more substantial impact.[42] Armenia, as well as Azerbaijan, lacked appropriate short-range air defense (SHORAD) assets.[43] Volume likely was also an issue. Azerbaijan saturated the airspace with many unmanned systems.[44]

It is possible that the success of Azerbaijan’s UAS in penetrating Armenian air defenses was, at least in part, due to several Armenian tactical blunders. Some systems operated without concealment. Many others were destroyed while in hiding, in transit, or were not operational.[45]

Despite Russia having a joint air defense agreement with Armenia and air defense assets at both the 102nd Military Base in Gyumri and the airbase at Erebuni, Russia appeared not to have intervened early on Armenia’s behalf. Russia did employ its Krasukha EW, possibly downing multiple Bayraktar TB2s, but this occurred late in the conflict.[46]

The limited use of combat aviation is also noteworthy, especially considering the Russian experience in Libya. After Turkish Bayraktar TB2s destroyed Russian-made Pantsir S-1 air defense systems, Russia transferred “MiG-29 fighters and two Su-24 attack jets” to Libya from its Khmeimim Airbase, near Idlib, Syria.[47] The Su-24 is a ground attack aircraft, but the MiG-29 is designed for air superiority and is capable of downing the Bayraktar TB2. Armenia did not use its own aircraft to defend against Azerbaijan’s UAS, likely from fear of losing them to Azerbaijani air defense systems and Turkey’s F-16s.[48]

The Land War

Key Points

The land war oscillated between maneuver and positional warfare. Azerbaijan’s repeated and coordinated use of UAS, loitering munitions, rocket artillery, and missiles enabled its ground forces to slowly take and hold territory, while denying Armenia the chance to adequately reinforce and resupply its beleaguered frontline forces.

The proliferation of sensors on the battlefield made it difficult for Armenian armor and other ground forces to conceal their positions. In addition, these formations lacked sufficient air defense capabilities and suffered inordinate losses as a result.

Both sides employed rocket artillery and missiles against military and non-military targets at various levels of war and from close fighting to strategic support zones. This indicated a lack of concern for collateral damage.

Turkey supplied Syrian fighters to support Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh, but their effect appeared negligible. Limited reporting indicated that volunteers from the Armenian diaspora might have participated as well.

Overview

Over a period of three decades, Armenian forces constructed layered defenses, often on superior terrain. However, they lacked the resources to hold the entirety of this line against sustained assault.[49] The night before the conflict, on September 27, Azerbaijani SOF inserted behind Armenian lines. During the ground assault that began the next day, primarily in the northern and southeastern portions of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijani helicopters inserted infantry with anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs).[50] Over the next several days, Azerbaijan conducted combined arms maneuver as armored formations attacked with supporting fires from artillery, UAS, and loitering munitions. Retreating Armenian forces responded with mines, grenade launchers, ATGMs, and artillery, inflicting considerable damage.[51] Days later, Armenian forces launched a counterattack, but its forces fell victim to UAS, loitering munitions, and artillery, because they lacked or had inadequate air defense for such threats.[52]

This pattern repeated itself throughout the remainder of the war.[53] The fighting alternated between maneuver and positional warfare, but ultimately Azerbaijan’s use of airstrikes and artillery prevailed. “This procedure was repeated day after day, chipping one Armenian position away each day and resupplying artillery during the night.”[54]

The remainder of this section examines armor, fires, and the use of foreign fighters.

Armor

Some analysts pointed to Armenia’s unsound employment of armor, such as the clustering of tanks and other vehicles and their lack of cover and concealment. They argued that such issues are the result of poor combined arms training.[55] Other analysts disagreed, noting the many documented instances of Armenian forces “digging in, concealing positions, and deploying decoys,” and adding that many armored vehicles were destroyed while maneuvering.[56]

It remains unclear the extent to which both sides may be correct in individual instances. This leads to a point on which all analysts agree—armored and other formations lacked sufficient protection from air threats, especially UAS and loitering munitions.[57] This is two-fold. First, is the necessity of layered, integrated air defense, including EW and C-UAS systems.[58] Second, is the evolution and proliferation of sensors on the modern battlefield, which make it increasingly difficult to conceal positions. A multitude of ever-evolving sensors make concealment challenging regardless of terrain, time of day, and other factors.[59] These are challenges for all militaries, not only those that fought in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Complete BDA figures are unavailable for many reasons, not least of which are the massive disinformation and misinformation campaigns discussed in the subsequent chapter. One analysis of video evidence provided some insights, albeit unconfirmed. Notably, these estimates do not include attacks on vehicles that were not recorded. The numbers are likely higher. Figures include:

Armenia: T-72 variants (136 destroyed and 4 damaged); armored fighting vehicles (25 destroyed); and various infantry fighting vehicles (21 destroyed and 1 damaged)

Azerbaijan: various T-72 and T-90 tanks (24 destroyed and 12 damaged); various armored fighting T-72 and T-90 variants (2 destroyed and 1 damaged); and various infantry fighting vehicles (20 destroyed and 3 damaged)[61]

Fires

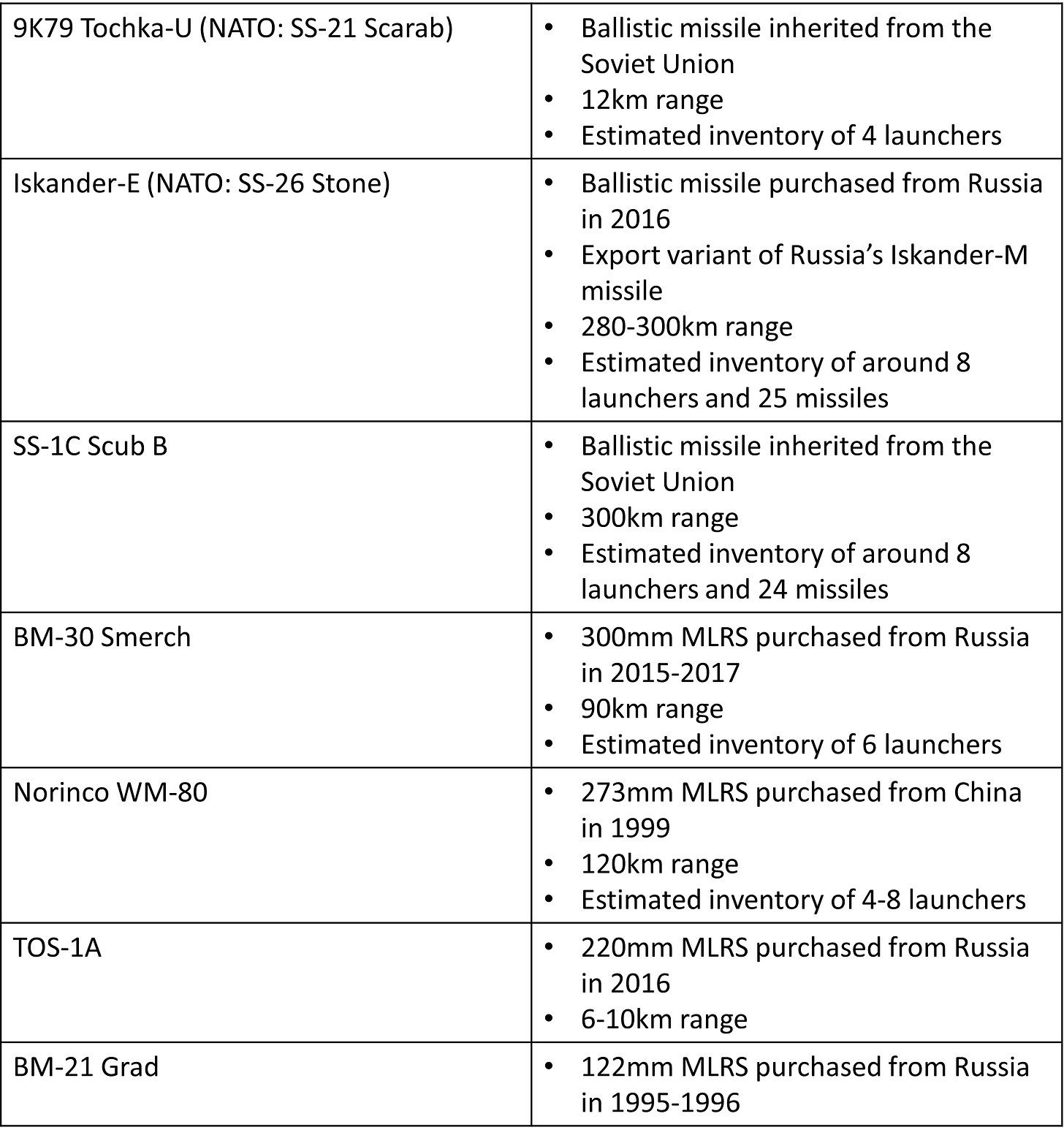

Armenia’s arsenal consisted of items inherited from the Soviet Union, as well as more recent purchases from Russia and China. The table below presents estimates of Armenia’s pre-war inventory.[62]

Table 3: Armenia’s Missiles and Rocket Artillery

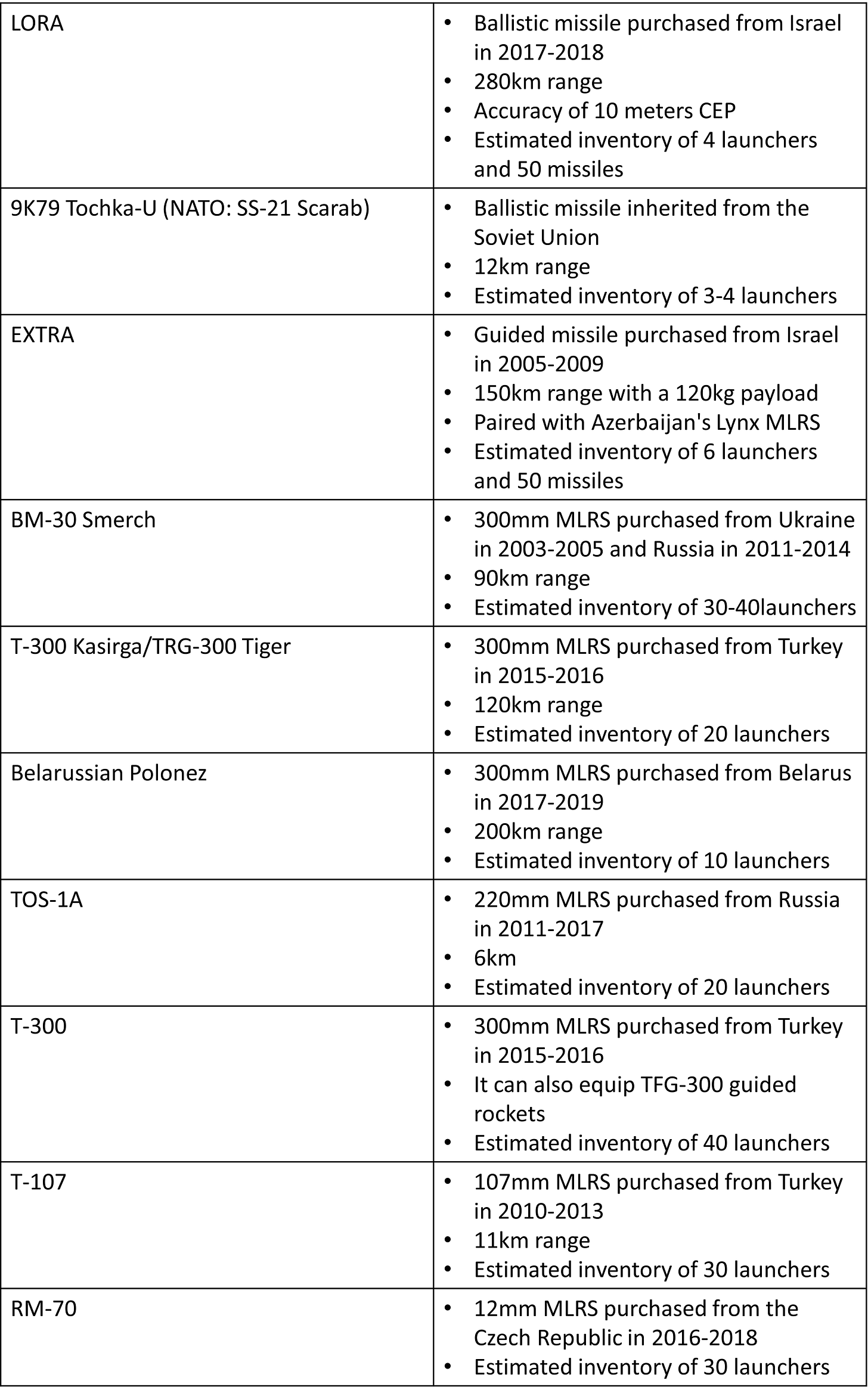

Azerbaijan’s inventory, in contrast, is generally newer and more varied, because of that country’s years-long military modernization efforts. The table below presents estimates of Azerbaijan’s pre-war inventory.[63]

Table 4: Azerbaijan’s Missiles and Rocket Artillery

Both sides extensively used the BM-30 Smerch and likely other Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS).[64] Similarly, both sides fired missiles. Armenia used the Tochka-U, Scud-B, and at least one Iskander-E.[65] Azerbaijan used the LORA missile to strike Armenia’s Ground Lines of Communication (GLOC) to “prevent the deployment of reserves and stall counteroffensives.”[66] Neither side used its full arsenal, especially the more advanced systems. The reason is unclear but may have to do with limited inventories and a desire to avoid escalation.[67]

Each side used fires, including cluster munitions, against non-military targets. Armenia conducted a series of strikes on the Azerbaijani cities of Ganja, Barda, and Gashalti. Azerbaijan repeatedly shelled Stepanakert, the “capital” of Nagorno-Karabakh.[68] In addition, each side accused the other of having used white phosphorus munitions.[69]

Foreign Fighters

Turkey/Azerbaijan

Turkey denies sending foreign fighters to aid Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh.[70] However, Turkey does have a history of employing foreign fighters—it sent Syrians to fight in Libya.[71] Despite Ankara’s denials, many governmental and non-governmental sources confirmed the presence of Turkish-backed Syrian fighters in Nagorno-Karabakh. For instance:

Senior representatives of the French, Russian, and Iranian governments all claimed Turkey supplied Syrians to Nagorno-Karabakh.[72]

Several prominent news outlets published interviews with Syrians who claimed to have been recruited by Turkey to fight in the conflict.[73]

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) published a detailed report of thousands of Syrians fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh.[74]

The Syrians that Turkey sent to Libya were “inexperienced, uneducated, and motivated by promises of considerable salary,” according to U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM).[75] SOHR reported similar findings in Nagorno-Karabakh. Turkish recruiters in some instances lured Syrians abroad with the promise of steady work and pay, without telling the Syrians the location or nature of the work. Some Syrians said they had no idea they were going to a warzone and were expected to fight.[76]

Armenia

This issue of Armenian-backed foreign fighters is less clear. Senior Turkish officials declared on the second day of fighting that Armenia was using “mercenaries and terrorists” from abroad, but Armenian leaders immediately denied the accusation.[77] At the conflict’s end, the Azerbaijani President claimed to have video and photographic evidence of foreign fighters from “France, the United States, Lebanon, Canada, Georgia and other countries.”[78] Some such assertions have been debunked. For example, one stated Iraqi Yazidis were fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh when they turned out to be Armenian Yazidis (nearly 30,000 live in Armenia.)[79] Nonetheless, other reports identified Armenian expatriates as combatants.[80] It remains unclear if Armenia and its separatist allies recruited foreign fighters. A more plausible explanation is that members of the vast Armenian diaspora might have gone to fight in Nagorno-Karabakh on their own accord. Such communities staged protests and made statements of solidarity in Russia, France, Belgium, Lebanon, and the United States.[81]

The Information War

Key Points

The information war was multifaceted, involving the governments of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey, as well as press outlets and legions of social media users. Both accurate and fabricated information proliferated globally throughout the conflict, leading to confusion at tactical, operational, and strategic levels.

For the entirety of the conflict, Azerbaijan selectively restricted Internet access, blocking most social media platforms inside the country. This represented the war’s most coordinated effort to control the information environment.

Azerbaijan’s use of UAS camera footage depicting strikes on Armenian vehicles and positions was the most visible element of the information war. However, the videos resulted in distorted views on battle damage assessment (BDA).

Cyber attacks were commonplace during the conflict, with attacks on government and private websites, as well as a potential attack on numerous flight tracking websites, possibly to obscure the movement of military aircraft at the onset of the war.

All sides engaged in “lawfare” to shape the information environment. Azerbaijan, by far, had the best coordinated, most wide-ranging effort.

Overview

The air and land wars were intense and consequential. However, these two should not overshadow the robust information war that occurred before, during, and after the conflict. The governments of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey all produced steady streams of information throughout the conflict. The same is true of countries not directly involved in the fighting, such as France, Russia, and the United States. The most prolific participant was the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense’s regular release of UAS camera footage showing the destruction of Armenian forces.

Senior Turkish officials and the bulk of the country’s press operated in tandem with the Azerbaijanis, releasing a daily deluge of anti-Armenia propaganda. Also, many Turkish civilians joined in the effort and displayed an outpouring of solidarity with Azerbaijan, particularly on Twitter. English translations of trending hashtags included “Azerbaijan is not alone,” “Either Nagorno Karabakh or death,” and “550 Armenians”—a celebration of reports that hundreds of Armenians had died in clashes up to that point.[82]

The Office of the Prime Minister of Armenia utilized the Armenian Unified Infocenter “to provide reliable and urgent information to the public in emergency situations.”[83] The Armenian tech community created the “Global Awareness Initiative” for a similar purpose.[84] Armenian social media users, both in the country and the diaspora, created “cyber armies” and “media fighters,” responsible for sharing and amplifying content.[85] Early in the war, Armenians even created a fake Twitter account for the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense, though Twitter later removed it.[86] In fact, misinformation was common to all sides.[87]

The following is a review of prominent themes encountered during the research for this project:

All sides (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey) regularly made disputed accusations of who started the conflict, as well as the necessity for self-defense.[88] Similarly, all parties made disputed claims about the commission of war crimes,[89] battle damage, casualties, and losses and gains of territories.[90] Lastly, to some extent, all framed the conflict in religious terms, as one of Islam versus Christianity.[91]

Armenia focused heavily on the issue of self-determination due to Nagorno-Karabakh’s majority ethnic Armenian population.[92]

Azerbaijan focused on Armenia’s occupation of Azerbaijani lands and associated historical and cultural ramification.[93]

Turkey regularly highlighted what it saw as anti-Turkish/Turkic sentiment[94] and a broader rift between the East and West.[95]

The remainder of this chapter examines the following topics in greater detail: Azerbaijan’s control of information; UAS camera footage; cyber attacks; and lawfare.

Azerbaijan’s Control of Information

From the day the conflict began, until two days after the final ceasefire, Azerbaijan placed restrictions on Internet activity within the country, ostensibly to prevent “large-scale provocations and cyber incidents committed by…[Armenia].”[96] NetBlocks, a non-governmental organization that promotes Internet freedom, released metrics to show that the “social media and communications platforms Facebook, WhatsApp, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, LinkedIn and Twitter, Zoom, Skype and Messenger” were unavailable in late September.[97] Azerbaijan later eased some restrictions, particularly on Twitter, which President Aliyev then used to message in English and Russian. Twitter is not popular in Azerbaijan, possibly due to users fear that the company will share data with the Azerbaijani government. Azerbaijan’s control of information amounted to a concerted effort both to restrict domestic access to information and to influence the international audiences.[98]

In practice, these steps did not completely block all users’ access to social media—many were still able to find and share information online—but the move represented the war’s most coordinated effort to control information. There was also self-censorship. Many Facebook pages typically critical of the Azerbaijani government abstained from criticizing authorities during the conflict. In addition, popular bloggers, “refrained from publishing any information not confirmed officially.”[99] Whether such restraint was heartfelt or done to avoid repercussions is unknown.

UAS Camera Footage

A hallmark of the conflict was the Azerbaijan Ministry of Defense’s use of UAS camera footage depicting strikes on Armenian vehicles and positions. The Ministry posted such videos daily on its website, tweeted and retweeted the videos, and even showed them on big screens in the country’s capital, Baku.[100] Azerbaijan likely learned this lesson from Turkey, which used a similar tactic to boast of its “aerial exploits in Syria and Libya.”[101] Some analysts believe such videos were, in part, an effort to distract from less favorable facts of the war, including the high number of casualties.[102] Despite the propaganda value of the videos, their actual content remains suspect. For instance, they likely exaggerated the numbers of Armenian vehicles destroyed.[103] Moreover, the global attention the videos garnered overshadowed BDA that was not caught on camera.

Cyber Attacks

Numerous cyber attacks occurred during the conflict. Most notably, the website of the Armenian Ministry of Defense was down on the second day of the war, which that government claimed was “for security reasons.”[104] The threat intelligence unit of Cisco, Talso, reported hackers breached “Azerbaijani government IT networks and [accessed] the diplomatic passports of certain officials” and that they used a fake Azerbaijani document to spread malicious code to steal data from compromised computers.[105] Separately, an Armenian group called the “Monte Melkonian Cyber Army” claimed responsibility for the attacks in a post on Facebook.[106] Azerbaijani hackers launched attacks, too, primarily against dozens of Armenian news websites.[107]

Lastly, the flight tracking services FlightAware, Flightradar24, and PlaneFinder all reported simultaneous disruptions at the start of the conflict. Though the companies refused to provide details, some claim it was a distributed denial of services (DDoS) attack, possibly aimed at hiding aircraft movements in the combat zone. Unconfirmed reports put the blame on the “Turkish Cyber Army,” which allegedly was responsible for an earlier attack on Google Earth.[108]

Lawfare

Though “lawfare” is not a doctrinal term in the U.S. military, the concept is applicable to this conflict, particularly as a means to influence global opinion. It remains unclear at this stage how much genuine legal action will result from the conflict and what, if any, meaningful consequences such processes might bring. It is clear, though, that threats of prosecution and appeals to multilateral organizations figured prominently in the information war as each side made legal claims to shape the public opinion in both domestic and international audiences.[109]

Azerbaijan engaged in lawfare extensively. From the outset, Azerbaijan framed the conflict as one of defense against Armenian aggression. Azerbaijani officials regularly cited international law, including United Nations Security Council resolutions, International Criminal Court standards, and the European Convention on Human Rights.[110] Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Emergency Service sent letters to peer organizations in roughly thirty countries and twenty international organizations. The letters detailed alleged “terror committed by the Armenian Armed Forces against the civilian population of Azerbaijan.”

[cxi] Azerbaijan’s General Prosecutor’s Office made detailed public claims of Armenian “war crimes throughout the conflict and declared the necessity for a military tribunal to prosecute such crimes.”[cxii] After the conflict ended, Azerbaijan announced its intention to use a state commission to prosecute war crimes and seek compensation for damages related to the destruction of property, not just during the most recent conflict, but for the entire thirty years of occupation.[cxiii]

Armenia’s legal response appeared less robust. Armenian leaders claimed publicly to be the victims of Azerbaijani and Turkish aggression, including war crimes, and appealed to international leaders.[cxiv] However, Armenia did not engage in the wide-ranging legal posturing as its opponents did. Armenia’s primary legal actions seem to be through the European Court on Human Rights where Armenia filed a complaint against Azerbaijan on the first day of fighting and another against Turkey one week later. Azerbaijan filed its own complaint in late October. As of early February 2020, these cases were ongoing.[cxv]

The End of Hostilities

Ceasefires

On October 5th, after a little more than a week of fighting, Azerbaijani President Aliyev, “demanded Armenia set a timetable to withdraw from the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, to recognize the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and to apologize to the Azerbaijani people.”[cxvi] In addition, Aliyev insisted Turkey be part of any peace process.[cxvii] Such conditions were wholly unacceptable to Armenia, a fact Aliyev almost certainly understood. At the same time, Iran proposed a ceasefire deal of its own, but it failed to gain traction.[cxviii] The fighting continued.

A Russian-brokered ceasefire was set to begin at noon local time on October 10th. However, each side immediately accused the other of violating the agreement and fighting continued once more.[cxix] On October 26, the U.S. and other Minsk Group member nations appeared to have revived the deal made on October 10 when Armenian and Azerbaijani officials, "reaffirmed their countries’ commitment to implement and abide by the humanitarian ceasefire agreed in Moscow."[cxx] This effort, too, was short-lived and fighting resumed minutes later.[cxxi]

Finally, on November 9th, the warring parties agreed to a Russian-led ceasefire that began the following day. The agreement allowed the exchange of prisoners and war dead, mandated that Armenia withdraw from lands not lost during the fighting, including various Azerbaijani territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, and created a corridor, “between Azerbaijan and its own landlocked exclave, known as Nakhichevan.”[cxxii] The agreement also called for the deployment of approximately 2,000 Russian peacekeepers.[cxxiii] The peacekeepers deployed a thirty-five-mile line that includes the Lachin corridor (see map on page 5.)[cxxiv] Lastly, following the ceasefire, Russia and Turkey agreed to create a joint operations center. The center became operational on January 30th and is staffed by sixty Russian and sixty Turkish personnel. The mission of the center is to monitor ceasefire violations, though little additional information is known at present.[cxxv]

Reactions

In response to the November 10th agreement, angry protestors immediately stormed the Armenian Parliament in Yerevan.[cxxvi] A genuine domestic political crisis ensued as protests continued for weeks and many Armenians demanded their president’s resignation. [cxxvii] In Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding territories Armenia had occupied, ethnic Armenians packed up their belongings and fled. Some even set fire to their houses rather than see their homes fall into Azerbaijan’s possession.[cxxviii]

In contrast, Azerbaijan and Turkey were jubilant. On December 10th, thousands of Azerbaijani troops participated in a victory parade in Baku. Presidents Aliyev and Erdogan were both present. The latter gave a speech in which he lauded the two countries’ successful cooperation in the conflict. [cxxix]1

Conclusion and Outlook

This product provided an open-source analysis of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War. This analysis was based on a broad body of government reports and press releases, media reports, and analyses from regional and topical experts. It addressed geopolitical and policy matters sparingly and only for contextual purposes. Rather, the report focused on new and otherwise significant uses of military technologies and tactics, as well as noteworthy vulnerabilities and shortcomings.

The following are noteworthy lessons learned for future conflicts:

A combination of UAS/loitering munitions provides much of the functionality of a traditional air force, but at a much lower cost. Therefore, such capabilities are no longer the purview of wealthy nations.

Many modern air defense systems are ineffective against slow-flying UAS/loitering munitions.

Sensors pervade the modern battlefield to such an extent that it is difficult to achieve effective cover and concealment, leaving ground formations vulnerable to detection and attack. Ground formations without organic air defenses, in particular C-UAS, likely will not survive this environment.

Long-range fires remain viable against frontline formations, operational reserves, and strategic support zones.

Information warfare is so pervasive it is difficult to separate fact from fiction.

Bibliography omitted due to length. Author maintains original copy.