“What are you saving this superb military for, Colin, if we can’t use it?”

-Madeleine Albright to Colin Powell

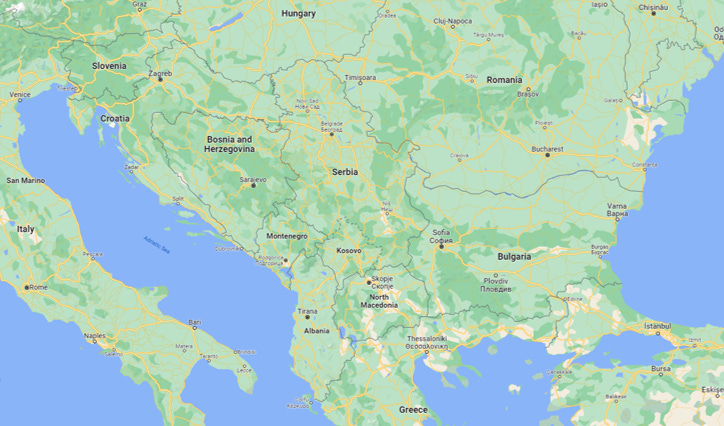

How many Westerners recall the last concentration camps in Europe were those of the 1990s, not the 1940s? The montage of European wars playing in the collective Western memory skips spottily from World War II to Ukraine. Hidden are the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Forgotten are the sieges, shelling, sniping, and ethnic cleansing. Mariupol became a colorized Stalingrad and, in between, not so much as a flicker of Vukovar, Sarajevo, or the Preševo Valley.

The ongoing war in Ukraine already casts a long shadow, even though no one knows how or when the war will resolve. One of the cyclical realities of history is that we always move in relation to some great undoing. The significance of today’s war has little to do with Donbas, Kherson, HIMARS, or any other ephemeral detail. This war is pivotal not because of the cards each player holds, but because the players have gone all-in on their respective grand designs. We face a momentous bend in history, around which we cannot presently see. Whatever comes next will be fundamentally different than the post-Cold War order.

We seem to have forgotten the troubles of the former Yugoslavia. This is unsurprising. Yes, digital life has truncated both our thoughts and our speech, but this region was always mystery to the wider world. For instance—and contrary to popular assumption—Communist-era Yugoslavia did not belong to the Eastern Bloc, and was not allied with the Soviet Union. Rather, its leader, Marshal Josip Broz Tito, championed the Non-Aligned Movement, and delighted in opportunities to play East against West—a recurring but typically short-lived opportunity for any leader of the South Slavic Land.

The most consequential feature of the region has always been its hapless geography, directly on the friction point between the Orient and the Occident. For nearly a millennium, locals found themselves on the frontlines of a succession of civilizational divides. There was the break between Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity as an eventual outgrowth of the missionary work Cyril and Methodius, the Greek brothers credited with delivering the Slavs both Christianity and an alphabet, Cyrillic. A vestige of this divide is clearly visible today. Even though Serbian and Croatian are fundamentally the same language, the former uses Cyrillic and the latter Latin.

Then, of course, came the centuries of intermittent war with the Ottomans, and the resulting injection of Islam into the region’s social fabric. In 1453, Mehmed the Conqueror seized Constantinople, changing its name to Istanbul, and changed the world’s largest church, the Hagia Sophia, into the world’s largest mosque. By this point, however, the Ottomans had long made their mark on what would become Yugoslavia. The Serb’s 1389 loss to the Ottomans at the Battle of Kosovo Polje is an enduring presence in the Serbian conscience, one they commemorated annually to this day—even though it was a catastrophic defeat.

The intervening centuries brought more of the same: domination by larger states; stunted revolutions; displacements and migrations; and competing claims on land, power, and legitimacy among the region’s rival sects. Major events led to catastrophic losses of life, but even the more minor, obscure episodes tended to be zero-sum and blood-soaked. At times, the former Yugoslavia became an industrial scale hellscape of ethnic murder, fueled by centuries of grievances, feuds, and dueling historical narratives.

In 1991, the former Yugoslavia began to break-up, producing a series of wars over the course of a decade. Slovenia fought a brief war, lasting only days and causing a few dozen casualties. Then Serbia and Croatia fought a much longer, costlier war. At the same time, there was a separate war between the Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats—though not entirely separate because the latter groups received support from the former. There were also the Bosniaks—Muslims who fought a separate war with Bosnian Croats after having been united with them against the Bosnian Serbs. Then came Kosovar Albanians, who were not the same as Albanians from Albania. Then came an Albanian insurgency in…Macedonia. You get the picture—or not, which is more to the point.

Over twenty years ago, a Croat offered to sell me his family land near Dubrovnik, but he insisted I would be responsible for demining. Much has changed since then. Of the seven nations of the former Yugoslavia, four belong to NATO and/or the EU. Our focus today is on the remaining three, especially Bosnia. After lengthy UN-backed NATO intervention, the war there concluded in 1995 by way of the Dayton Accords. This peace was always tenuous, particularly for the Bosnian Serb entity which has long wished to secede and, possibly, join with neighboring Serbia. Secession seemed to most outside observers a fantasy because NATO and the EU simply wouldn’t allow it—they would intervene to enforce status quo of Dayton, as they long had.

The world faces a five-headed hydra of fiscal, monetary, economic, energy, and food crises (if not others.) Global credit and liquidity are evaporating. The result will be bankruptcies, for sure, but probably sovereign debt crises, too. Such emergencies are not new, but they rarely hit the West with the force of these coming events. Recall Ukraine, which consumes massive quantities of money, weapons, and other assistance from the West. Modern Europe has yet to endure its first hard winter, and historic hardship is sure to occur across the Atlantic.

The Western appetite for foreign intervention survives only in times of plenty. I find it unlikely Bosnian Serbs would forgo an opportunity to secede with their Euro-Atlantic minders focused inwardly. What then of a Bosnian Serb referendum to join with Serbia, particularly with ethnic plebiscites now common in Eastern Europe? What then of peace between Serbia and Kosovo? After all, the latter exists only as the result of NATO’s 1999 war on Serbia and the Clinton Administration’s penchant for picking winners (and losers).

In late February, I wrote an explainer of the Russia/Ukraine war for the consulting network, Poligage, where I am a member of the expert network. It concludes with a look beyond Ukraine, to the Balkans, where Russia has long sought to undermine the West’s post-Cold War presence. I noted then it was too early to draw conclusions. That observation remains valid now, but the arc of Balkan history is long and bends toward vengeance.

(This piece belongs to the thematic series, “Western Leadership and Other Myths.”)

The title is in reference to a joke I’ve heard in various forms. It tells the story of “the Croat, the Muslim, and two Serbs who found themselves on the moon. The Croat claimed it for the Croats, because the barren landscape resembled the mountains of Dalmacia. The Muslim claimed it for the Muslims, because its shades of grey were exactly those of the hills and escarpments of central Bosnia. One of the Serbs then took out his revolver an shot the other. ‘Now the moon is Serbian,’ he said for wherever a Serb has spilt his blood or lies buried is forever Serbian territory.”

Madeline Albright died on 3/23/2022. This article’s cover photo is 3/24/2022, on the anniversary of NATO’s war on Serbia. Even twenty-three years on, their anger is palpable.

Madeleine Albright, Madam Secretary: A Memoir, September 16, 2003, p.182. (epigraph)